Road Is Losing. Gravel Is Winning. Here Are the Numbers.

If you followed our State of the Sport Series on the To Be Determined Journal, you probably read our attempts to analyze and understand the trends that are shaping cycling today. In one of our most recent State of the Sport pieces we asked What Happens When Gravel and Road Racing Collide? As it turns out, that post touched a nerve in the cycling community - provoking a lot of thoughtful commentary on our various social channels. Based on feedback from fellow racers and race organizers we decided to analyze data from one of the best-run gravel events in the country—Rasputitsa—to see what we could learn about its riders and their registration trends over time across road cycling, gravel, cyclocross and more.

The Data: 123,303 registrations for 2,729 riders

With Rasputitsa’s permission we partnered with BikeReg to source an anonymized set of data containing all Bikereg registration history for Rasputitsa riders since 2000. The data set we got back was huge—containing 123,303 race registrations for 2,729 riders—including more than 2,200 men and nearly 500 women. With this massive collection of data points in hand, we compiled a few key questions that we hoped to answer:

How quickly is Rasputitsa growing?

Rasputitsa has a well-articulated focus on bringing more women and youth riders to their event. Is this admirable focus adding more women and juniors to traditional bike racing in the process?

Is Rasputitsa an inflection point for riders? After doing Rasputitsa, do riders race (on the road or cyclocross) more or less? What happens to gravel participation levels after riders participate in their first Rasputitsa?

Perhaps most importantly, what conclusions can we draw about the broader impact of gravel events on road racing and cyclocross?

Part One: Rasputitsa and the Rise of Gravel

In 2016, Rasputitsa had its third consecutive year of modest growth – reaching just over 600 riders up compared to 515 the previous year. That’s not bad for an event started by two friends and held across cold, muddy roads in Vermont in April.

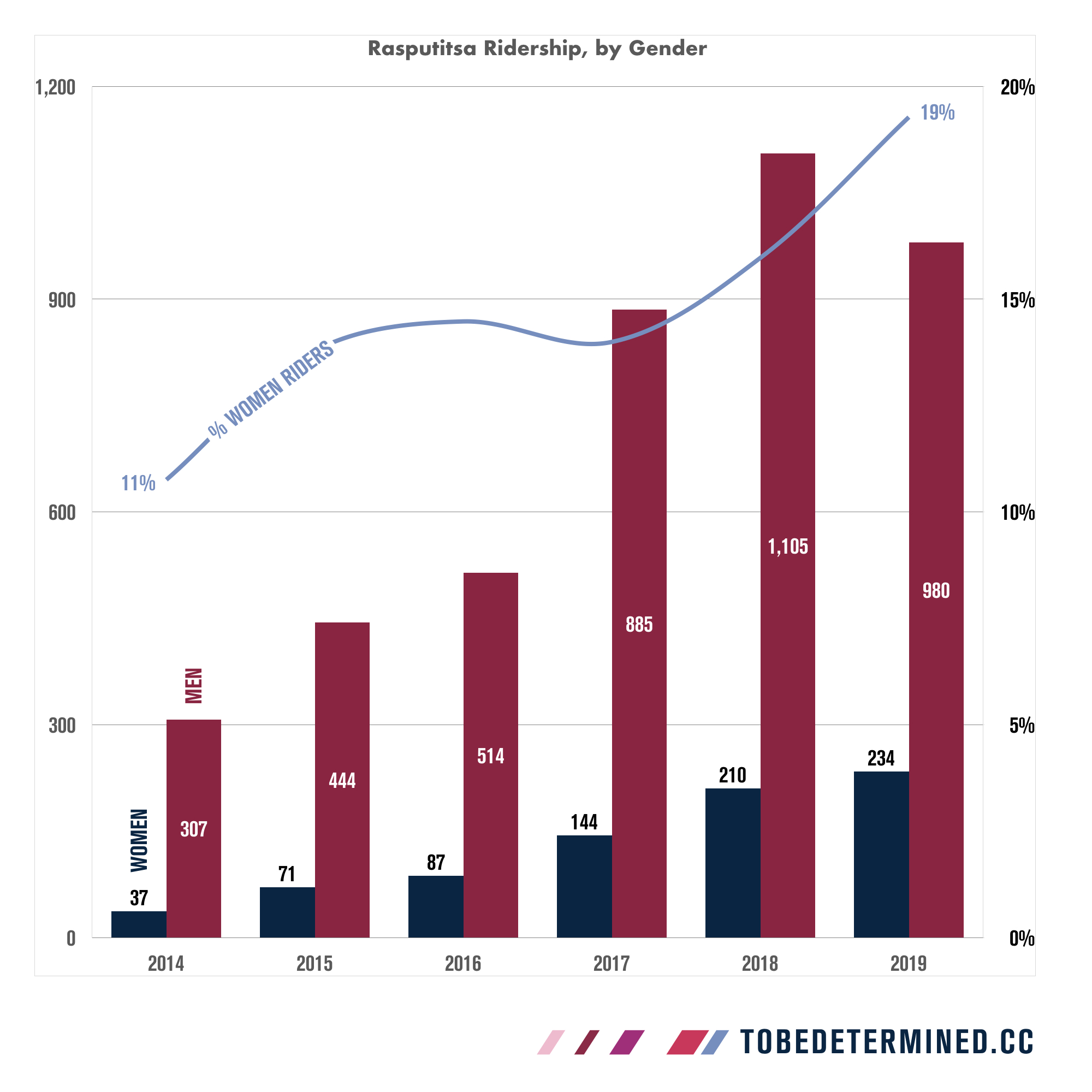

By last year, Rasputitsa more than doubled in size from 2016—hitting an incredible 1,315 riders (this is 2x the entire racing membership of CRCA). During that same period, women’s ridership increased 141%, and 2019 looks to continue the trend of increasing women’s attendance. About 20% of riders at Rasputitsa this year will be women if current registration patterns hold:

It’s fair to say that this type of growth would be good for any type of athletic event. But when compared to what’s going on in road cycling, it’s astonishing. For example, last year’s count of new women members to CRCA road racing was the club’s lowest since 2009—only about 25 new women joined the club (women typically only comprise 15% of new CRCA members). Meanwhile, Rasputitsa added almost three times that figure year-over-year in 2018, and 2019 seems poised to add further new women to the ranks.

Part Two: The Gravel Inflection Point

Here is what the gravel boom looks like on a graph. It includes all riders who have ever participated in Rasputitsa, and shows their participation in any event categorized as road, cyclocross or gravel in a given year.

The “rider” figure above represents the count of people who raced any event within a category (e.g. cyclocross) during a calendar year. An individual rider may count in multiple categories if that rider participated in each category.

Among all Rasputitsa riders, gravel registrations skyrocketed from 2014 onward. What’s also remarkable is how much road declined during the same period. According to this data, road racing “peaked” in 2014 among Rasputitsa riders. That year, 824 riders raced on the road. By 2018, fewer than half the 2014 total registered for any road event. Cyclocross has been more resilient, seeing modest declines since hitting its apex among the Rasputitsa population in 2016, but the contrast in gravel participation and non-gravel participation is remarkable.

The question on our mind, once we saw the chart above, was whether the year someone first participated in Rasputitsa represented an inflection point in these riders’ amateur careers.

To find out, we built an index that looks at ridership among everyone who raced Rasputitsa, and compared their attendance in road, cyclocross and gravel events before and after doing the event. Year zero in the chart represents the year someone first did Rasputitsa; year one represents one year after their first year (regardless of whether they returned to Rasputitsa); and so on. We also omitted Rasputitsa itself from this dataset to observe how these riders behaved outside of the event – again, before and after having attended for the first time.

This is what we found:

Among riders who raced Rasputitsa in 2014-2016, virtually all of them continued to do other gravel events in the following two years—and gravel/dirt/fondo events represented one of their top “event types” among all cycling activities. Their participation in cyclocross racing declined very slightly—with about 8% of riders quitting cross the year following their first Rasputitsa. But road was a very different, starker story. The number of riders who raced road declined 45% in the year following “year 0”, and the road number dropped another 37% the following year (shown as "year 2” in each chart).

In terms of race-days, the data is similar. Road race days declined 43% in the year following each rider’s first Rasputitsa, while gravel registrations increased. Notably cyclocross remained the dominant race format among the total Rasputitsa population—though total race days still declined by 28% over the two years following riders’ first time Rasputitsa participation:

The “race day” figure above represents the count of total event registrations in each category across all riders who first raced Rasputitsa in 2014-2016.

Another trend we noted in the data: Most riders tended to first participate in Rasputitsa on or near the apex of their cycling careers—the year the greatest number of riders registered for the most events and participated across the most disciplines (e.g. road, cyclocross and gravel events). In other words, year -1, year 0, and year 1 in the Rasputitsa index tend to be when most riders are participating most in cycling. And as we’ve also documented in “The Abbreviated Life of a Bicycle Racer,” people usually aren’t bike racers for long. Attrition following a rider’s first few years in the sport is severe—and only a fraction of people continue racing more than a few years following their first year in the sport. The Rasputitsa population fits in line with this analysis, with road cycling seeing a relatively high abandonment rate in years’ following these riders’ “apex” year. It’s for this reason that we cannot assume gravel is causing the decline in road, though it’s certainly a possible factor.

Conversely, the single most remarkable thing about this data is that gravel seems to be immune from the attrition seen in road. In fact even as riders quit road and cross in years following “year 0,” those same riders are participating in more gravel events. The obvious caveat is that it is still early days for gravel as underscored by the massive growth in Rasputitsa participation in 2017/2018. As gravel matures these trends will evolve, but for now the divergence in attrition observed in the current dataset indicates that thus far gravel does a better job retaining event participants than road or ‘cross.

Part Three: How the Gravel Inflection Point Varies by Demographic

We broke down this data to see whether certain age groups or genders displayed a different reaction to what we have coined the ‘gravel inflection point.’ The short answer is: all pools of riders that we examined demonstrated similar patterns to those above, albeit with some interesting twists.

Among women, we saw declines in cyclocross participation over time, both pre- and post-Ras, while like the broader pool, gravel ridership and race days increased following these riders’ first Rasputitsa. Road race-days also declined among women following the first Rasputitsa participation, though the decline is less dramatic than for the overall population. Said differently, women who participate in Rasputitsa continue to participate in road racing at a higher rate than do men who participate in Rasputitsa.

We also analyzed riders of all genders who were in their “prime” years to start racing, to see if any age bias existed in the data. In other words, we examined people who were unlikely to “age out of the sport.” Based on those who were ages 23-29 during their first Rasputitsa, the answer appears to be “no.” Gravel still increased its rider participation over time among this age group while road racing and cyclocross saw declines. We note that this is a relatively small sample size relative to the charts above.

A similar trend followed among U23 riders, where road race-days plummeted in the years following a rider’s first Rasputitsa, declining by more than half and generally mirroring the attrition rates that we wrote about in the Abbreviated Lifecycle of a Bike Racer.

So with some modest differences, key demographic pools appear to mirror the trends observed in the overall data set: the shift toward gravel is strong across all subsets with women showing the lowest rate of road racing attrition following participation in Rasputitsa (a data point that seems noteworthy given road racing’s struggle to attract more women to the sport).

Part Four: Conclusions on How Gravel Changes Road Racing

The math, laid out simply, tells this story: After riders first attend at Rasputitsa and start racing gravel, it’s likely that half of them will quit road the following year.

It’s at this point that we should make a note about not assuming causation because there is correlation. What this data does not say is “Gravel Kills Road.” What it does suggest is that around the same time that riders in this pool started to quit racing road and scaled back their race days, they also tended to do much more gravel racing. Is it possible that there is cause-and-effect at play here? Absolutely. But it’s equally possible that, as we note above, the reason why road declines is simply a function of coincidental burn-out in the already short racing lifetime of a cyclist.

One inescapable conclusion, however, is that Rasputitsa is doing something really right—something that is arguably missing from many road events. Perhaps it’s the production value: the views; the food; the camaraderie among an increasingly diverse group of participants. Or perhaps it’s that they’re trying to break down barriers around women’s participation and support charitable causes.

But real talk—the road racing numbers from this analysis and our other coverage portend a difficult future for the sport. We will continue to do more soul searching to explore what we, as road racers, can and need to do to reverse the trend. We’ll save those theories for future State of the Sport entries, but in the meantime you tell us: comment, Tweet, or email us your thoughts, and we’ll take them into account as we plot future essays. We already started another analysis that we expect to finish in the next few weeks, so stay tuned.

Until then, see you on the road (and on the gravel—we’ll be on the start line at Rasputitsa 2019 in just a few weeks).

Transparency statement

BikeReg and Rasputitsa gave us permission to use the data with no qualifiers on the analysis that we ran or the opinions that we expressed. We had complete editorial discretion and greatly appreciate their support. The data involved was completely anonymized by BikeReg before we received it, and Rasputitsa agreed to the disclosure because they “are committed to growing cycling in all aspects and believe truth and data will only foster conversation and reflection,” said Heidi Myers, co-founder of Rasputitsa.

Definitions

The “gravel” category includes the following BikeReg event types: ‘Gravel Grinder,’ ‘Off Road’, ‘Fat Bike’, and ‘Gran Fondo’. We included ‘Fondos’ because they’re mass-start events that fairly count among the types of events we’re thinking compete against categorized races or conversely drive interest in racing; even though they aren’t explicitly “gravel” or “off-road” or “dirt” events. There are also only 979 total registrations for Gran Fondos from 2000 to 2019 among the total Rasputitsa population, across 478 riders—a relatively small percentage of the total population of gravel cohort.

Update: Michele on Twitter raised a great question about why we added the BikeReg “Fat bike” and “Off-road” event types — which include MTB events — to our gravel definition. It’s a fair point, and I didn’t really address it well above.

The answer is that we're largely using gravel as a catch-all term. The root of our questions about the state of the sport are how events like Rasputitsa—Is a ride? is it a competitive race? Is it a dirt event or a gravel event or a snow event? Depends on who you ask—affect traditional road cycling (and to a lesser extent, cyclocross). So, obviously 'Gravel Grinder' would be included, but we also thought it made sense to include other dirt events like ‘fat bike’ and events in the 'off-road' category to see if there were patterns in riders shifting "away" from road/cross and toward these other event types.

The other consideration is that labeling a given event with an "event type" in BikeReg seems to be discretionary to each promoter. And, scrolling through the "off-road" events, we saw a wide variety of dirt event types in there—many non-competitive, non-USAC categorized, 'fun' events like Rasputitsa or 'dirt-grinder' type rides are included. That's exactly what we think competes with traditional road racing. It's also true that the “off-road” category includes classic categorized MTB like DH, XC, etc with your H2H-type races. But frankly, that was Ok in our book as a point of comparison against the road calendar as well.

That said, to make sure this inclusion wasn't biasing the data one direction or another, we did do some analysis of the population with "off-road" excluded from the 'gravel' category to see if changed the outcomes of the model ... but it didn't. In fact, with 'off-road' excluded, the slope of the "Gravel Grinder" category's growth is even greater.

Anyway, a lot of this comes down subjective opinions on the definition of what we think is changing in the sport. Should we have excluded it? :shrug: We could next time if folks' want us too. But it wouldn't have made a difference in the outcome of this story. Thanks for asking!

Contributors: Clay Parker Jones and Matthew Vandivort