An Hour in Flushing: The First 30

This article is the first part of a two-part series on breaking the Kissena Hour Record. The First 30 describes the emotional side of things, what to expect physically, and the background of Kissena Velodrome. For everything technical, the Second 30 will be coming soon.

While this post does not get into the gear, I would be remiss not to mention the tireless (and entirely voluntary) work that Jason Gallacher of Affinity Cycles. More on him and the equipment later, but I just gotta give the man props here.

You’ll hear that an hour record is the purest effort in cycling. Let me quickly explain this because it’s kind of a biggie. An hour record is the furthest distance you can travel in an hour. Or, the highest speed you can travel at for an hour– it’s the same thing. (More people than you’d think don’t get this.) “Oh you’re doing an hour record, how long does that take?” “An hour.” “Oh.” The hour has a rich history in cycling that I won’t get into here, but for now, all you need to know is you get a bike, a course, and 60 minutes. It doesn’t matter if you’re Pippo Ganna or some bozo like me, it won’t end any quicker. An hour is an hour is an hour…

10 minutes to go.

I had been warned that the last ten minutes of an hour record attempt were the toughest. You’re deep in a lactate hole as you desperately cling to the uncomfortable position you’ve been in for 50 minutes. All the while, you know that any deviation, any raggedness, is only going to slow you down. All you can do is try to stay as relaxed as possible and focus on the basics. The ribbon of paint racing beneath you and the count you’ve held for the last 90 laps. ‘200m line, one pedal stroke, two pedal stroke, three pedal stroke, left turn… Start line, one pedal stroke, two pedal stroke, three pedal stroke, left turn…’

So it was a bit of a surprise that for those last ten minutes of my attempt at the Kissena hour record, I couldn’t stop smiling.

Let me quickly set the scene. To do that, we need to go back. Way back. To 1962, when urban planner, New York legend and guy-who-once-tried-to-build-a-literal-highway-through-downtown-Manhattan, Robert Moses, had the idea to construct a velodrome on Booth Memorial Boulevard in Queens as part of the showcase for the World Fair later that year.

“Sgtm” said the city.

Robert Moses probably approving Kissena park or something.

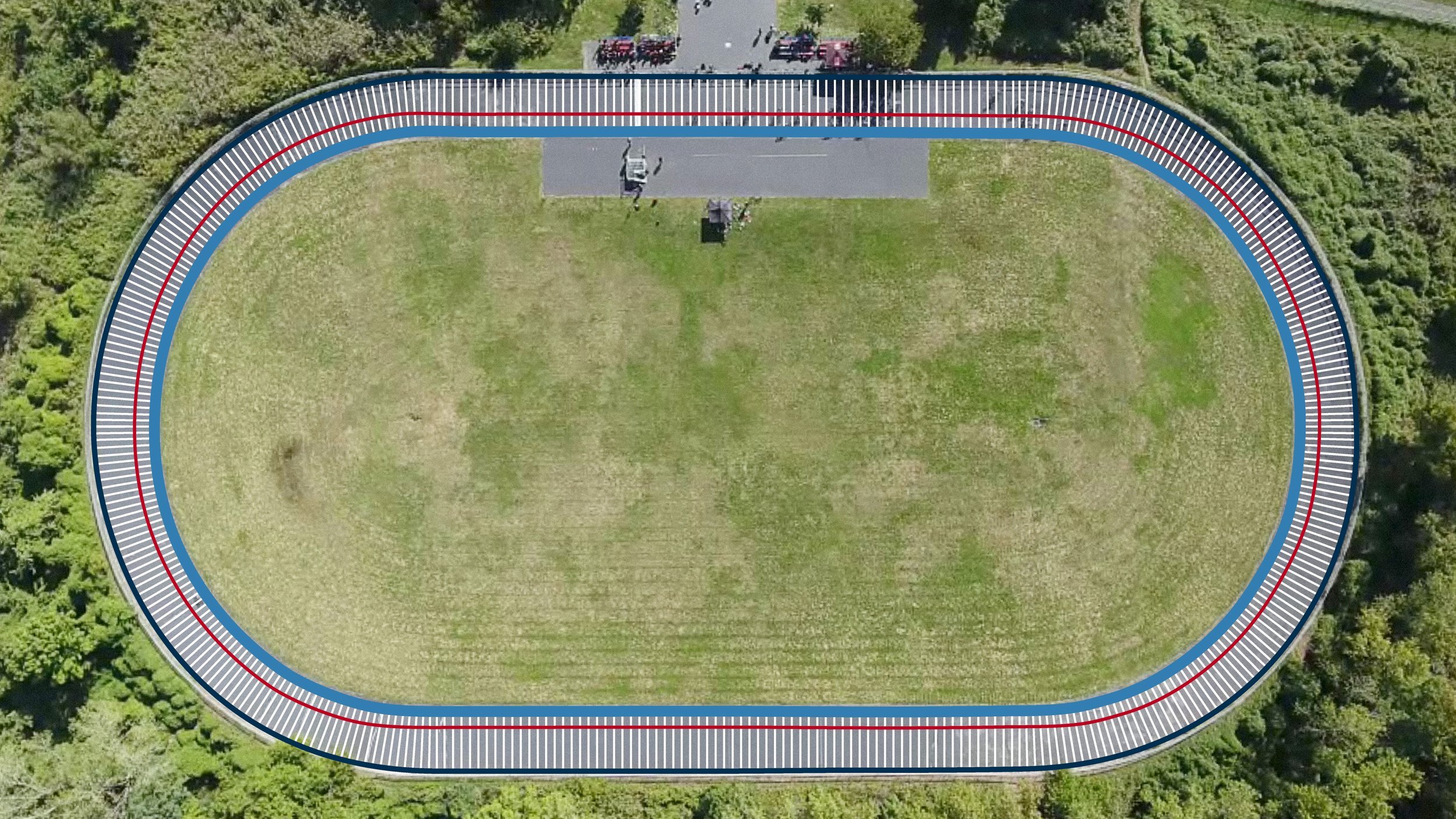

And so, a 400-meter loop of asphalt, with 15-degree banking (hardly anything in track cycling terms) came to Queens. It was cracked and bumpy and a perfect encapsulation of the city it was to represent. In other words, it was imperfect, but it was New York’s; to this day, it’s still the only velodrome in the whole state.

Throughout its life, Kissena has been used for everything from Olympic trials to grassroots cycling initiatives. But through it all, it has stayed the beating heart of New York’s biking culture. Today, it’s the venue for the indispensable work of Trackfam who host races and clinics at the track every weekend. I’d wager more racers have cut their teeth on Kissena’s bumpy asphalt than any other place in New York.

Which brings us to Ken Harris.

It’s August, 2008. A sunny, windless day at the track. Set against the blue sky, a young man wearing a bright orange jumpsuit and sipping from a beer wrapped in a paper bag is conducting an interview. He thrusts his microphone at a second man. This second man is tall, burly, you could say for a cyclist. He wears a teardrop helmet and a skinsuit emblazoned with his team’s name, Jonathan Adler Racing. He is smiling comfortably, like he’s entertained by the whole bit. This is Ken Harris.

“Ken, you’re attempting to break the Kissena hour record, how many laps are you shooting for?”

“111.” The response comes without pause. It’s not boastful or optimistic, just a calm statement of fact.

“111.”

I’m told by people that know him that this is Ken’s vibe– a calm, eccentric guy who knew how strong he was. (I heard that to prepare for this, he tied ribbons to himself and cycled in front of a fan to simulate the effects of wind tunnel testing.)

This whole conversation goes down in a 10-minute left-side-audio-only video titled, ‘Ken Harris breaks the Kissena Track hour record’. In it, two of Ken’s teammates goof around in a mock news segment, the whole thing is charmingly vintage YouTube. Then, Ken gets on his bike and proceeds to ride 27.4 miles (44.2kms) in laps of the velodrome over the course of an hour, setting a benchmark that would stand for 14 years, and in the process, creating the Kissena hour record.

At first, the record first stood as a testament to the kind of fucked up stuff people can do on bikes and the myth of Ken Harris grew. “Did you know he did 450 watts for an hour?” But gradually, people moved, people stopped racing and, for the most part, the record was forgotten. Save for a few stalwarts of the scene and one 360p video online.

This is where my dumbass comes in.

It’s October, 2021. I’m sitting on the curb outside Paulie Gee’s slice shop in Greenpoint, surrounded by other muddy attendees of Keith Garrison’s weekly cross practice. We’re talking about this and that when Keith mentions the Ken Harris record. I remember being shocked.

“27 miles?”

“Don’t encourage him, he’s dumb enough to try it.” friend of TBD, Mark Steffen, chimed in.

He was joking but he was right. It was a small moment but it was enough to sow the seed. Here we had the only velodrome in New York state, the heart of the community, a place that had trained olympians and the record seems so… attainable I guess? Not easy, but I was shocked that the hour record wasn’t more of a thing. It should be! This should be something someone tries at least once a year.

Anyway, that’s more or less how I decided to take on this big dumb project.

It turns out doing an hour record starts with emailing a bunch of people. Over the course of the next several months, I sent dozens of emails to various USAC affiliated parties, introducing myself, explaining what I was doing and, in one case, explaining that miles per hour is the same thing as miles in an hour. The details aren’t important, but to give you a usable piece of info, you need two USAC officials present and Jeff Poulin (who is a true mensch) is the man to help you.

In my head, I had the idea of doing this sometime in mid-to-late September. The weather would be warm but not too hot, you get the occasional nice, low pressure day and I would still be carrying a good deal of road fitness. Lovely jubbly. The emails continued, more people got involved, USAC was jazzed, the team was jazzed, word got out and the wider community, too, became jazzed.

Which brings us to late August, about two weeks from the day, and a slight problem had started to emerge. I still didn’t have a bike. See, in order for a record to be official, it needed to be completed on a bike with track gearing. And, in order for me to have any hope of actually beating the record, I needed an aero cockpit. What I needed was a pursuit bike– which is a fairly specialized piece of kit.

Throughout the course of the year, I had been trying to track a bike down but one by one my scant leads and dried up. Also, If I’m to be very brutal with myself, I wasn’t trying THAT hard to find one. But now we were two weeks out and I either needed to find one or this was not going to happen. I hadn't anticipated that finding the bike would be the hardest part of this challenge.

It was then that I received an email from Jason Gallacher of Affinity cycles. As the head of Trackfam (the organization responsible for organizing events at the track as well as recent renovation efforts) I had already emailed Jason but since I had not heard back, I had assumed he wasn’t interested. (Which is fine! After, I’m just some bozo...) But his email told me that nothing could be further from the truth. Jason wasn’t disinterested, he was also jazzed! We quickly arranged a call and set up a time for me to come to his studio where he would set me up with a bike. On the phone, Jason was passionate and clearly knew absolutely everything about gearing and aero that I had no clue about– and had spared no thought for. Jason was exactly the guy I had been looking for.

We met up at Jason’s the week after Green Mountain Stage Race– my final road race of the year. There, Jason quickly got me on a bike and began to dial my position in with a practiced eye. About an hour into our meeting, he asked me,

“So you must ride track bikes a lot, huh?”

“Actually” I responded “I’ve been trying to see how long I could avoid that question. I’ve never ridden a fixed gear bike before.”

“Oh.” He was thoughtful for a minute. “Well, you should practice!”

The response that came wasn’t judgemental. He didn’t seem put off. It was just an observation. A calm statement of fact.

At the time, it meant a huge amount that he was so welcoming and still believed that this big, dumb idea was possible, even if I had never ridden a track bike before. The more I have gotten to know the track racing community, the more I have realised that this is the default. Road racing can sometimes be guilty of being a liiiittle exclusive, but in track, the more the merrier! I saw myself as a bit of an interloper, but to Jason, I was just a new person to hang out with. I really needed that as I was only just understanding how moronically out of my depth I was.

Two weeks to go.

It turns out, Jason was right. I did need practice. In the months leading up to September, I had done routine tests, just to make sure that I could actually do the speed and power required and that I wasn’t going to make a complete fool of myself. But once I was on the pursuit bike, it was totally different.

For one thing, you quite simply cannot ride a pursuit bike on the streets. The gear is too big to slow down effectively and the bars feel incredibly precarious on crowded roads. I spent the first few nights just doing laps of the big concrete area by McCarren park, relearning to ride a bike. Then there’s the position. I had been practicing by trying to get as aero as possible on my road bike, but scrunching yourself onto the skis feels pretty unusual.

Once I felt comfortable moving on the bike, I graduated to going down to the track early in the mornings. (Hot tip, owning a car makes doing an hour record way easier because remember, you can’t ride your bike on the streets anymore and Kissena park is a long way from the city! My solution was to take Lyft XLs every morning before work, which was a bad idea and expensive!) My plan was to get as many laps in as possible before the day.

My first time at the track it was pitch dark (Hot tip 2: the track is not illuminated!) It was just me and the raccoons. Oh well, I was here and it’s not like I could ride home, so I’d have to do my session as planned. I started doing laps guided by my little bike light.

This was easily my lowest point in the entire project. In the dark on a track I had never ridden, the bumps were throwing me all over the place, I could barely hit 25 mph and fuck knew what was beyond the scant glow of my headlight– if a raccoon stepped out I was just going to hit it, I guess. At one point, I lost my focus for a split second and came off the inside of the track and onto the grass while I was still in the skis. The attempt was in ten days and I could barely ride the machine. I took a long minute and slowly swallowed the rising feeling of panic and the desire to quit.

‘Just do one good lap.’ I told myself. ‘It doesn’t have to be fast, it just has to be good.’ If you can do one good lap, you can do another good lap after that.

Slowly, things started to improve. Really, it didn’t matter if it was dark or not. In the aero position you’re not looking up anyway. All you need to see is the pursuiter’s line on the floor in front of you. By the time the sun had risen, I was stringing together good laps and my earlier wobble was behind me.

One week to go.

Something I would say is essential to getting something like this done is to surround yourself with the best people you can find. I was incredibly fortunate to have with me my great friends and teammates Alvaro, Cullen, and Scott, who gave up their time and expertise in spreadsheets to help me out.

A decision we made pretty early on was that I should do a trial run the week before the attempt. This would be a full hour, at attempt pace, in the position. This would help us get the timing dialed in (more on that in part 2) but more importantly, I would help me get the ‘oh my god this fucking sucks’ dialed in.

And boy did it fucking suck!

We did it on a bright, windless Saturday morning that would have been perfect for the real thing. I warmed up on my road bike and then did a few laps on the track bike. One thing that became clear quite quickly was that the helmet was causing some issues. The plastic visor was cutting into my eyes, causing them to tear up. So, I did away with it.

Then, we had one last quick chat about timing. The plan was to have Cullen, Alvaro and Scott on a conference call. Two would sit at the start line recording lap times and entering them into a spreadsheet that would predict my finishing distance. Then, these two would communicate the lap time to the third man who was standing 200m down the track. When I would pass this person would yell my previous lap time to me in the form of the one and the tenth. So, for example, a 31.8 second lap would be yelled to me as “1 - 8!”

It sounds bonkers but it works surprisingly well– with a fixed gear on a flat surface in a position you can’t change, there are basically no variables. You really do begin to learn the difference between a 31.8 lap and a 32.0 just on feel.

Now it was time. The dress rehearsal. I squared up to the start line with butterflies. We had all agreed together that we weren’t going to put any pressure on this day… but we had all privately decided that this was absolutely going to be the day.

It was not the day. Sort of. In the end I was about 10 meters short of the record. That said, my average speed was a good kilometer over the required pace which means I had done a bad job of sticking to the pursuiter’s line. In a pursuit, you’re following the painted line that traces the shortest distance around the track. Any deviation from that line adds distance you don’t get credit for. It might not sound like much, but over an hour, a deviation of one foot can add 400m to the distance you need to cover.

In that sense, the test did its job. I had shown I could do it, learned what I needed to improve on and started to learn the sections that would cause me problems (20 minutes in and 35-40 minutes in). Over that distance, ten meters was not a lot to make up. Putting a proper skinsuit on should sort that out. All that was left to do was to do the damn thing.

3 hours to go.

It sounds anticlimactic but there wasn’t much to the day of the record itself. All the work had already been done. Cullen picked me up early and we drove down to the track together. There, we set up the timekeeping table, swept the leaves off the track and waited for the USAC officials to roll up. The weather was flat and grey and the air pressure was low. Ideal conditions in a boring way.

I busied myself with warming up and tried not to think too much about the start. More people than I had expected came down to have a look, which was heartwarming but didn’t do a tonne for my nerves.

Honestly, given the pages of writing that have lead to this point, I wish I had more to say about the attempt itself, but the truth is I don’t remember much of the first portion. An hour is both a very long and a very brief time.

I had a quick chat with the officials, received some last pieces of advice from Jason, spoke with the timekeeping guys and, at a little after 7am, I set off.

The first 20 minutes passed pretty quickly. Every lap was marked with a doppler-shifted wave of cheers, followed shortly by Scott’s lap times, bellowed through the megaphone he had brought. Adrenaline takes care of this patch, the biggest challenge is making sure you don’t go too deep too early. It’s incredibly difficult to repay anything once you put yourself into debt for these kinds of effort— ideally, you want to be right at your limit but never over it (which takes practice).

At the 20 minute mark I hit my first spot of trouble. 20 minutes is always a problem for me– far in enough that you’re really hurting, but still 40 minutes from finishing. At this point, there’s not a lot you can do. Some people tell you to power through, but I prefer to think of it as waiting. Just wait. You’re doing the power you need to do, your body can take it. It’s your mind that’s labouring. Just wait and your mind will change.

At around 30 minutes that rough period starts to ease. You’re more than halfway.

At 35 minutes, I hit another rough patch. This time I gave myself a time goal. ‘Think about how much better 45 minutes will sound than 35 minutes. You can hang on for 10 minutes.’

After that, the next stop is 15 minutes. 15 minutes has always been a huge marker for me. That’s two race laps of Prospect Park, it feels like a very manageable amount of time. This was the first time this thing felt properly possible. I was urging the bike forwards with every fibre of my being.

So here we were.

10 minutes to go.

‘200m line, one pedal stroke, two pedal stroke, three pedal stroke, left turn… Start line, one pedal stroke, two pedal stroke, three pedal stroke, left turn…’

Sometime in those last ten minutes, someone in the crowd told the others to spread out all around the track. Up to that point, the cheers had come as one compressed wave, now they were coming every ten meters. I still couldn’t look up but I was able to distinguish individual voices and make out what people were saying. Then, the sun came out.

Riding through that last section was difficult to describe. I’ve been sitting here for a while now and I still haven’t found a good way of capturing it except to say that I’ve never experienced anything like it before and likely won’t again. But I will remember it forever. Knowing I had it, passing all my friends, in this special place of all places. To my lactate-addled brain, it felt like riding into heaven or something… all I could do was smile.

“Is he… smiling??” I managed to make out as I passed. Then…

“2-9!”

32.9. That was off the pace. I was letting my emotions get the better of me, I still hadn’t finished yet. I focused on getting back on top of the gear and keeping things smooth.

Coming into my final lap I had been told beforehand that I should cross the finish line and then keep going until I heard the whistle, but hearing the cheers I looked up and eased off slightly, only to hear Scott screaming at me to keep going.

Another half lap and I was done. The whistle blew, I sat up and yelled something. I started crying almost immediately, more out of relief than anything else. I was surprised how quickly they escaped from me. You can watch the last 3 minutes here.

Coming around the final corner and rolling to a halt I practically fell off the bike and into the waiting Big Agnes chair someone had deployed. (We are open to chair sponsors, BA!) I don’t remember much about what followed, I think someone offered me some Dunkin’ and I got the official distance: 44.540km, about a lap more than the previous record. 111 laps.

It was done, I was done.

Kissena velodrome was originally built as a celebration of New York. It was a monument erected by an unelected official, on marshland, slowly sinking into the ocean. It’s cracked and bumpy, and the fourth corner will try to kill you. By all accounts, it should have been paved over and redeveloped, or, at the very least, have been replaced with facilities for a more popular sport. But somehow, it has defiantly remained a symbol of cycling in the city. It nurtured community, it nurtured champions and it nurtured friendships even as it slid into the Long Island Sound, what could be more New York than that?

I have always maintained that I didn’t care about whether or not I broke the record, nor did I want to set a record that stood for another 14 years. That would have been nice but to make that the sole focus would be to miss the point. To my mind, failure would be folks forgetting about this. My dream, I told people, was to make the hour at Kissena “a thing.” There’s plenty of room for it, after all. I’d be thrilled if someone came along and tried to top this–– I’ll give you advice, I’ll keep time for you, I’ll cheer you on during your final ten minutes. Nothing would make me happier, because I think this velodrome and this community are worth 60 terrible minutes.

To that end, I’d like to once again plug the ongoing efforts of Jason and Trackfam to refurbish the track. Without him and without Trackfam, there would be no Kissena velodrome. Thanks, Jason.